In Clinical

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

Key facts

- Many people with diabetes cannot detect the warning signs that herald hypoglycaemia

- Older people seem less likely than younger people to realise they are hypoglycaemic

- Real-time continuous glucose monitoring has been found to reduce the risk of hypoglycaemic events by 72 per cent

In 1919, a nurse had to sleep alongside her patient to detect and rapidly treat nocturnal hypoglycaemia. The young girl in question had type 1 diabetes and was one of the first people to receive insulin.

The nurse saved the child’s life “dozens of times” using orange juice or molasses.1 Today, more than a century after insulin’s discovery, the problems posed by hypoglycaemia persist.

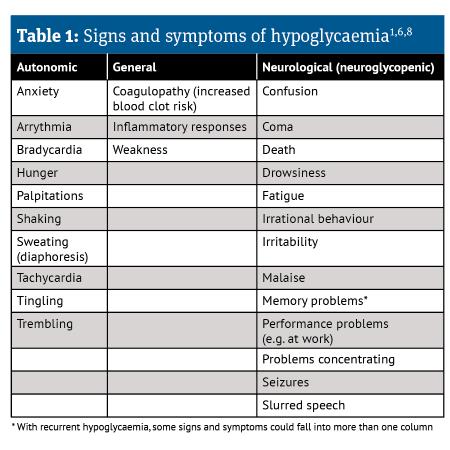

Hypoglycaemia causes various signs and symptoms (see table), undermines quality of life, limits occupational choices and is often distressing for friends and families. Unfortunately, many people with diabetes cannot detect the warning signs that herald hypoglycaemia.

This impaired awareness of hypoglycaemia (IAH) increases the risk of severe hypoglycaemia six-fold in type 1 diabetes patients and 17-fold in people with type 2 diabetes who are taking insulin.1 So how can community pharmacy teams help break the IAH cycle?

Common issue

Epidemiological estimates do vary, but IAH is common among people with diabetes:

- A Scottish study reported that 19.5 per cent of 518 adult type 1 diabetes patients attending a hospital diabetes clinic had IAH2

- A meta-analysis of nine studies suggested that 22 per cent of people with type 2 diabetes experience IAH3

- Another recent study found that 23.2 per cent of 56 people with diabetes receiving haemodialysis had IAH. Rates of IAH were 3.6 and 19.6 per cent in those with type 1 and type 2 diabetes respectively.4

Some patients seem to be at particularly high risk of developing IAH. “Clinically, IAH is most common in people who have had diabetes for a long time and those with type 1 diabetes or those with type 2 diabetes taking insulin,” says Samina Ali, advanced practice pharmacist and diabetes specialist pharmacist, NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde.

Complex insulin regimens are more likely than simpler courses to induce IAH.3 Other anti-diabetic drugs, notably sulfonylureas, can also cause IAH.3 Pharmacists could consider such risk factors when talking to patients with diabetes.

Several other factors make IAH more likely, including comorbidities, especially those treated with drugs that affect glucose levels.3 A Japanese study reported that diabetic peripheral neuropathy almost trebled (odds ratio 2.63) IAH risk.5 Older people seem to be less likely than younger people to realise that they are hypoglycaemic.3

“Many patients still do not fully appreciate the risks of hypoglycaemia”

The Scottish study found that, compared with patients with normal hypoglycaemia awareness, people with IAH were significantly older (mean 39.3 and 45.9 years respectively) and had a longer duration of diabetes (median 14 and 23 years respectively). Participants with IAH were also six times more likely to have experienced severe hypoglycaemia during the previous year.2

Several biological mechanisms contribute to IAH including changes in the brain’s ability to sense glucose levels and impaired hormonal counter-regulation. Hypoglycaemia triggers the release of, for instance, glucagon, adrenaline and growth hormone, which cause blood glucose levels to rise. In people with IAH this hormonal counter-regulation seems weakened.6

“Repeated episodes of hypoglycaemia can impair the counter-regulatory system in response to falling glucose levels, potentially leading to the development of IAH,” Ali adds. Brain scans also reveal changes in regions linked with appetite, emotion, aversion, recall, arousal and decision- making in people with IAH and recurrent severe hypoglycaemia.1

Reducing the risk

The introduction of glucose monitoring empowers people with diabetes with unprecedented control over their blood sugar levels. “Continuous and flash glucose monitoring reduce the number of hypos. The alarm alerts the user of a possible impending hypo, enabling them to act accordingly,” Ali says.

In the six-month HypoDE study, for example, real-time continuous glucose monitoring reduced the mean number of hypoglycaemic events from 10.8 to 3.5 per 28 days in people with type 1 diabetes receiving multiple daily insulin injections. The participants had experienced IAH or severe hypoglycaemia in the previous year.

Control patients who wore an inactive monitor showed a “negligible” fall from 14.4 to 13.7 hypoglycaemic events per 28 days. So real-time continuous glucose monitoring reduced the risk of hypoglycaemic events by 72 per cent.7 “The action the patient needs to take depends on the trend arrow.

For example, if the person has been alerted that their glucose levels are 5.5mmol/L and the arrow is pointing downwards, they will need to take 5-10g of fast-acting carbs, such as one or two jelly babies, and recheck their glucose after 10 to 15 minutes,” Ali explains. “Pharmacists should ensure patients know how to interpret the results.”

Pharmacy teams also need to be vigilant for evidence of IAH, says Ali. “They should be especially alert for IAH in people with a long duration of diabetes and on insulin. A lack of test strips ordering if they don’t use continuous or flash glucose monitoring, presenting with hypo symptoms and recurrent ordering of hypo-treatment products, such as Glucogel, may also possibly indicate IAH,” Ali suggests.

“Community pharmacists and their teams should also advise a patient experiencing recurring hypos to see their GP or diabetes team.”

About half of severe hypoglycaemic episodes occur at night, which may impair awareness during the following day1, so the anti-diabetic regimen needs to control blood glucose levels throughout the day.

Modern regimens, drugs and monitoring all reduce the risk of hypoglycaemia. Yet many people do not, it seems, fully appreciate hypoglycaemia’s risk, live with IAH, or both. By remaining aware of IAH and tackling the misconceptions, community pharmacists and their teams can help further reduce the impact of hypoglycaemia on the lives

of patients and their families.

References

1. Diabetologica 2021; 64:963-970

2. Diabetic Medicine 2008; 25:501-4

3. Acta Diabetologica 2023; 60:1155-1169

4. BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care 2024; 12: DOI: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2023-003730

5. Diabetol Metab Syndr 2023; 15:79

6. Biomedicines 2024; 12: DOI: 10.3390/biomedicines12020391

7. Lancet 2018; 391:1367-1377

8. Diabetes & Primary Care 2023; 25:157-9